Talking to the Dead

Not only can I still have a conversation with my dead dad, I can't avoid having a conversation with my dead dad.

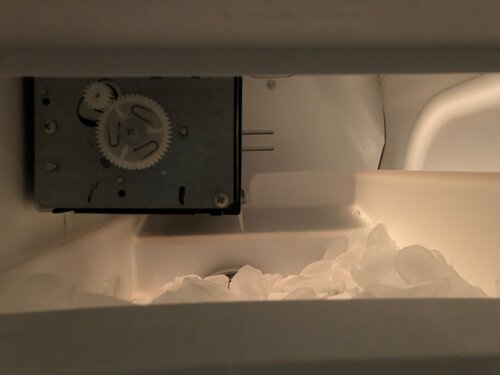

A few months ago, we moved to a new apartment here in Brooklyn. I was absolutely shocked to find that the suburbs-sized fridge contained an ice maker.

Though you non-New Yorkers probably aren't impressed, I'd not encountered this particular amenity since departing my childhood home in the suburbs of Atlanta about 15 years ago.

The ice maker soldiered on like a champ for about a month. During that honeymoon period, the pandemic heated up and New York got locked down, so simple domestic pleasures came to loom large in our lives. I couldn't have my nanny, my coworking space, or a cocktail in a bar - but at least this beautiful, effortless ice kept coming.

But soon there arose trouble in ice paradise. Increasingly, I had to manually pry off cubes that had frozen to the ice maker's plastic fingers, thwarting the process mid-cycle. Then the ice became puny and hollow. A few times, we tried to dispense some cubes and nothing fell out at all.

While my dad was dying, I somehow became exposed to the line of thought that a relationship does not genuinely end with the death of one half.

It was probably via David Kessler, a colleague of the late Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who writes extensively on grief. I had attended an event of his at the New York Open Center back in the fall of 2018, pregnant and full of apprehension about visiting my dad for his upcoming final birthday.

At first, this "relationships survive death" idea struck me as impossibly cheesy. Ok, so the relationship isn't technically over - but that's just semantics. The dead person is still gone. Good relationships are a two-way street. So if there's some relationship left with a dead person, then at the very least it's inherently dysfunctional.

But as I tinkered with this stupid fucking ice maker, I thought over and over of my ultra-handy dad. I imagined visiting him again and telling him about my ice maker troubles. He'd tell me about times he'd fixed our family's ice maker in the past. He'd hold out his medium-large hands with those sort of flat fingernails and explain to me how an ice maker works.

I remember the very last time he explained something mechanical to me, with his hands, from the corner suite of the cancer ward of a shiny new hospital off Georgia state route 400. It was something about how car engine technology has improved, and the arrangement of the pistons. He held his hands out in the usual manner and I knew it was the last time, unfolding right before my eyes. I started crying. He asked me what was wrong and I told him that I like the way he explains things. The moment passed, like moments do. And that was that.

So here I am now, a year and a half later, realizing my ignorance. Not only can I still have a conversation with my dead dad, I can't avoid having a conversation with my dead dad. I will keep hosting this ice maker conversation until the damn thing is completely fixed.

I've tinkered with water and temperature settings, replaced the water filter, used a hair dryer to unfreeze the parts, etc. The ice maker unfroze, then flooded itself with so much water the ice started crashing out in big glacial sheets. I monitor the situation and use my screwdriver to adjust the water level bit by bit. The ice is almost perfect again.

My dad didn't understand people very well, but he understood every machine. I partially understand people and I partially understand machines. I understand this ice maker just enough to coax it back into operation. And I understand my dad just enough for him to take up post-mortem residence in my head.

Pamela J. Hobart - Philosophical Life Coaching Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.